Over 10% of the U.S. population— more than 34 million individuals— lives with diabetes, with 1.5 million new cases diagnosed each year. As people with diabetes manage this chronic condition, they often pay substantial amounts out of their own pockets on medical care and prescription medications. Using HCCI's unique health care claims dataset, this brief illustrates the impact of diabetes on the use of and spending on health care services among individuals under the age of 65 who have employer-sponsored insurance.

Even in this population with health insurance, we find that people diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes spent more than $1,000 out-of-pocket on medical services in 2020, nearly double the average out-of-pocket spending among individuals without diagnosed diabetes ($1,117 vs. $613). Our data also show that the rate of diagnosed diabetes in this population grew over 40% between 2016 and 2020, with the largest increase in the young adult population (ages 18-34).

Total and Out-of-Pocket Spending was Substantially Higher among People with Diagnosed Diabetes than those without

As shown in Figure 1, per capita medical spending was substantially higher among people with diagnosed diabetes than among those without diagnosed diabetes. In 2020, average total spending among those diagnosed diabetes was $12,296, compared to $4,233 among individuals without diabetes. The biggest difference in spending between those with and without diagnosed diabetes was among children under the age of 18 ($12,002 among those with compared to $2,633 among those without).

Similarly, as shown in Figure 2, average out-of-pocket medical spending was higher among individuals with diabetes than those without in all age groups. Overall, individuals with diabetes spent $1,117 out-of-pocket in 2020 compared to an average of $613 out-of-pocket among individuals without diabetes. Families with children diagnosed with diabetes had higher out-of-pocket costs than other age groups; these families paid nearly four times more out-of-pocket on medical care for their child than those whose children were not diagnosed with diabetes ($1,454 per year on average compared to $365). This difference in spending between individuals under age 18 with and without diagnosed diabetes was the largest among all age groups.

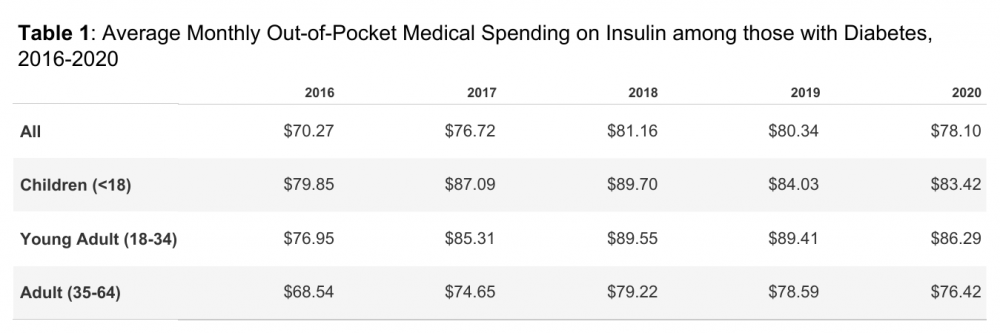

Average Monthly Out-Of-Pocket Spending on Insulin Increased by More than 10% from 2016-2020 and was Highest among Young Adults

Overall, average monthly spending on insulin was $78 in 2020. Young adults aged 18-34 had the highest average monthly out-of-pocket spending on insulin compared to other age groups, spending an average of $86 monthly on insulin, compared to children ($83) and adults ($76) (Table 1). Average monthly spending on insulin increased 14% over 2016-2019, with a slight drop in 2020.

Consistent with previous work, monthly spending on insulin was highest in January and fell over the year among all age groups, likely due to health plan deductibles being met as the year progressed (Figure 3). Across age groups, spending in December ($58) was almost half of spending in January ($112). January and February spending was highest among families with children under the age of 18; for the remainder of the year, young adults had the highest monthly average out-of-pocket spending on insulin.

Children Diagnosed with Diabetes are Three Times More likely to go to the Emergency Room than other Children

People in our data who were diagnosed with diabetes used many more health care services than those who were not diagnosed with diabetes. As shown in Figure 4, among the full population, 95% of those diagnosed with diabetes used at least one health care service, compared to 74% of those without diabetes.

Individuals with diabetes were nearly twice as likely to have an emergency room visit than those without diabetes (close to 20% compared to 9.5%). The difference in emergency room visits was especially notable for children; 22% of children with diagnosed diabetes had an emergency room visit compared to 8% of children without diagnosed diabetes. Young adults with diabetes were also much more likely to have had an emergency room visit compared to young adults without diabetes (25% of those with diabetes had an emergency room visit compared to 10% of those without diabetes).

Overall, a greater percent of those with diabetes had a primary care physician visit (69%) than those without diabetes (46%). Young adults faced the greatest differential in primary care; close to 60% of young adults with diabetes had a primary care visit compared to just 35% of young adults without diabetes. In fact, young adults, both with and without diagnosed diabetes, were the least likely to report a primary care visit compared to other age groups, though emergency room use was higher. Close to 25% of young adults with diabetes had an emergency room visit, compared to 19% of adults with diabetes.

Use of Diabetes-Related Emergency Services and Inpatient Admissions

Among individuals with diabetes, we also examined emergency room (ER) visits and hospitalizations directly related to diabetes (i.e., ER visits with a diagnosis code of diabetes and hospitalizations with specific diabetes-related DRGs). As shown in Figure 5, about 11% of all individuals with diagnosed diabetes had an emergency room visit related to diabetes. Rates for children and young adults were higher--about 14% in both age groups had a diabetes-related ER visit in 2020--compared to 10% among adults.

As shown in Figure 5, children with diagnosed diabetes were almost 20 times as likely to have a hospitalization related to diabetes than adults with diabetes (9% of children with diabetes had a hospitalization related to diabetes compared to 0.5% of adults). Young adults were also much more likely than adults to have a diabetes-related hospitalization, close to 3% compared to 0.5% among adults.

Data Highlights Need to Address High Insulin and Service Prices and Monitor Trends among Young Adults

HCCI's data show that people diagnosed with diabetes had out-of-pocket costs that were nearly double the average out-of-pocket cost among people without diabetes over the 2016-2020 period. A major component of these costs is insulin. Insulin costs have risen more than 10% from 2016-2020, driven by rising point-of-sale prices. Out-of-pocket caps or other policies to reduce the financial burden on individuals have been implemented in a number of states and proposed nationally. These types of policies can help reduce out-of-pocket costs while facilitating ongoing access to this critical medication but do not address the underlying issue of high prices and must be carefully designed to avoid unintended consequences that may drive up spending in the long-term.

Our results suggest that it is important to monitor the growing rate of diabetes diagnosis among young adults. Though their absolute diagnosis rate is low, it has grown faster than in other age groups. This population also is more likely to have an emergency room visit and is less likely to have a primary care visit than other age groups. They also have the highest spending on insulin of all age groups. Moreover, the young adult population faces a unique set of challenges, including transitioning from pediatric to adult health care providers, changes in coverage between their parents' insurance and insurance provided by a university or employer, and a higher uninsured rate relative to other age groups. Being un- or under-insured puts these young adults at high risk for adverse financial and clinical outcomes, especially among young adults with chronic conditions such as diabetes. For example, existing evidence has shown that young adults are especially likely to ration insulin due to financial instability, which can lead to major health consequences and even death.

This data brief highlights the burden of chronic disease costs among individuals with employer-sponsored insurance. Even among this population with health insurance, out-of-pocket costs among people diagnosed with diabetes are high, especially when compared to individuals without diabetes. The trends we observe in our data are likely more extreme for people without insurance, leading to missed care and poorer health. Policymakers have sought opportunities to address rising insulin costs; these efforts should continue and be complemented by broader efforts to lower service prices, which can result in lower overall out-of-pocket costs for individuals.

Methods

In this brief, we identified individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the employer-sponsored insurance population under age 65. We limited our sample to those who had a claim for diabetes-related medical treatment filed with an insurance provider.

An individual was considered to have a diabetes diagnosis if they met one of the following conditions: a) had one inpatient claim with a diabetes diagnosis, b) had two outpatient or carrier claims with a diabetes diagnosis, or c) had one outpatient or carrier claim with a diabetes diagnosis along with a prescription for insulin.

The rate of diagnosed diabetes is the percent of membership months in which individuals in each group were diagnosed with diabetes (Table). This was calculated as the number of weighted member months with diabetes divided by the total number of weighted member months in the sample. Once a member was identified as having a diabetes diagnosis, they were considered to have diabetes for all subsequent months of enrollment from the first date of diagnosis. Weighting was consistent with the approach and weights used in HCCI's Health Care Cost and Utilization report.

Table. Rate of Diagnosed Diabetes over Time by Age Group

| Age Group |

2016 Weighted Percentage |

2017 Weighted Percentage |

2018 Weighted Percentage | 2019 Weighted Percentage | 2020 Weighted Percentage | Percent Change 2016-2020 |

| All Ages |

3.29 |

4.16 |

4.42 | 4.56 | 4.64 | 41.03% |

| Children (<18) | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 4.35% |

| Young Adults (18-34) | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 46.27% |

| Adult (35-64) | 5.90 | 7.49 | 7.94 | 8.19 | 8.41 | 42.54% |

Use of any health care service was defined as the presence of at least one claim for medical services within the calendar year. Primary care and emergency room visits were defined as at least one claim with a BETOS code that indicated the corresponding service type. Diabetes-related hospitalizations were identified with DRG codes 637, 638, and 639. Diabetes-related ER visits included any ER visits with a diabetes diagnosis.